A Brief History of Great Paxton Church

You don't need to be a church goer to appreciate the history represented by a church. There is much social history here of the people whose lives were intertwined with the institution and the building, with numerous frequently enigmatic clues about the past that are held within the fabric.

There are several churches in England with a Saxon pedigree, though Holy Trinity Church Great Paxton is one of very few actual Saxon churches and the only one with two aisles, there is none other quite like it. It was built in the late Saxon era and the only similar churches are from the 10th and 11th century on the Continent, particularly in Germany.

Records about the history of the church are often not clear or simply absent, leaving us to make educated guesses and suppositions as to why things are the way we see them today. There are a number of unanswered questions about the building which has undergone some very significant changes throughout its history.

Building the church, construction in 1020

The church was built during the rule of King Cnut (Canute). At that time there were no parish churches as there are today and it would have been a "Minster" with several clergy and a head priest. These would have gone out into the surrounding countryside to conduct sermons as and when the opportunity arose. It was still a time of active conversion of the population at the end of the largely pagan Anglo-Saxon period. Such minsters were sometimes established in remote villages rather than in larger population centres. There is no record of exactly why a minster was established at Great Paxton (then simply "Paxton" as Little Paxton didn't exist) but Cnut was known for making widespread and generous ecumenical gifts and it may have been a result of this.

At that time stone buildings were rare, so the church will have represented a very significant construction in a small village with a largely subsistence farming population living in simple single-storey houses of wattle and daub with thatched roofs. There is no good local building stone and the basic construction of the church is of "clunch", a style commonly found across eastern England and Normandy. This consists of irregular large stones found locally in the fields (most commonly chalk or limestone, though not found at Great Paxton) used to build a wall and held together with lime mortar. Wooden boards a few feet long are placed to form a section of wall, the space is filled with stones and then mortar added and left to set before moving the boards further along. This is a slow technique and it would have probably taken a number of years to build up the walls for the church. If you look closely at the exterior walls, you can see that different parts have different inclusions of stone, being presumably what had been brought to the building site at that time. If you know what you are looking for it is possible to determine which sections were laid during the winter or the summer, so taking different amounts of time for the mortar to set.

The corners are of "dressed stone" that has been worked and cut to shape to give a good finish. This came from a quarry at Barnack (worked out by 1460) between Stamford and Peterborough. It is a kind of limestone also used to build Peterborough and Ely cathedrals, and will have been brought to Great Paxton via the river.

As well as requiring dressed and rough stone, the construction of the church will have required the making of large quantities of lime mortar which was otherwise at the time not needed for anything else within the village, so requiring new industrial capacity nearby.

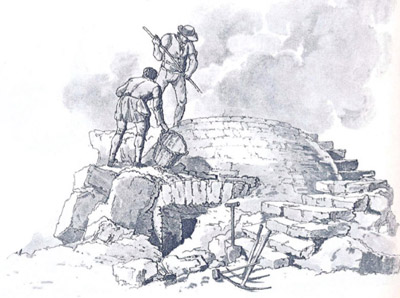

In 1934 an archeological excavation was made in a meadow between the church and river following the unearthing of pottery sherds when ploughing. This found what was thought to be the base of ancient limekilns and artifacts found surrounding the area date back broadly to the time when the church was being constructed suggesting they were used to make the mortar to build the church. All the artifacts found were those that men would have used and none were found that may have been used by women or children at the time indicating a place of work rather than of a domestic purpose. Limestone or chalk will have been brought in by river as there is no local source. While the land is dry now, prior to the drainage of the fens in the 1700's this area would have been on the edge of a water meadow stretching down to the river and it would have been possible to dig a ditch to work a small barge (or shallow punt-like boat) to the slightly raised area at the edge of the water meadow where the kilns were found.

Layers of fuel, wood, charcoal or coal, were interspersed with layers of chalk or limestone which would have been built up in the kiln and then set alight to slowly burn for days or longer before the lime which was formed was dug out and used to make mortar for the construction of the church. There was no other call for lime at that time and it would have been expensive to get the raw materials and make any more, so once the kilns were no longer needed for the church, they would have fallen into disuse.

The Original Minster and Subsequent Changes

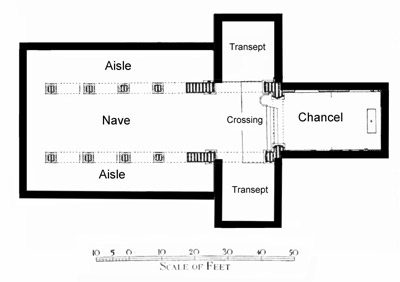

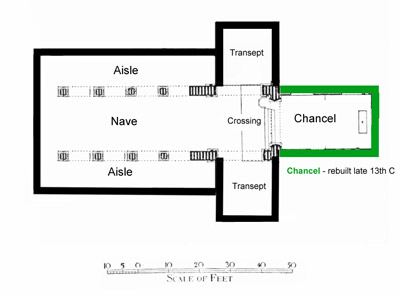

The original Saxon church is at the heart of the building that stands today though most of what you see from the outside was added in the following centuries. When it was built, the minster was cruciform (cross shaped) and somewhat larger than today. The tower stands at what would have been the base of the cross with the side-arms (the transepts) extending from immediately before the chancel to the north and south. It is the south side of the church that is shown in most pictures. The lower roof to the right (east) is of the chancel (the head of the cross) and while it is probably about the same size as the original, it was rebuilt towards the end of the 1200's. The original may have been apsidal (semi-circular at the end) rather than rectangular as this was more common in Saxon churches of the era, though there is no evidence either way.

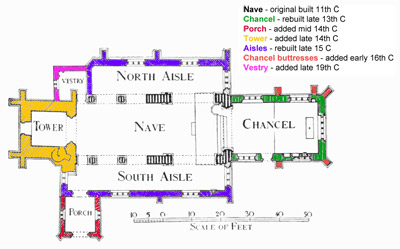

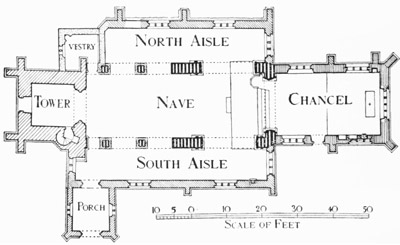

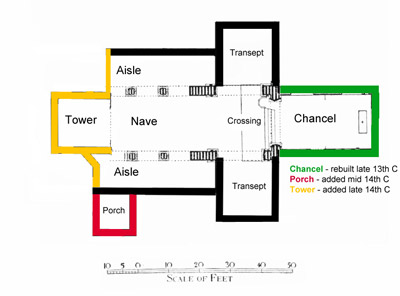

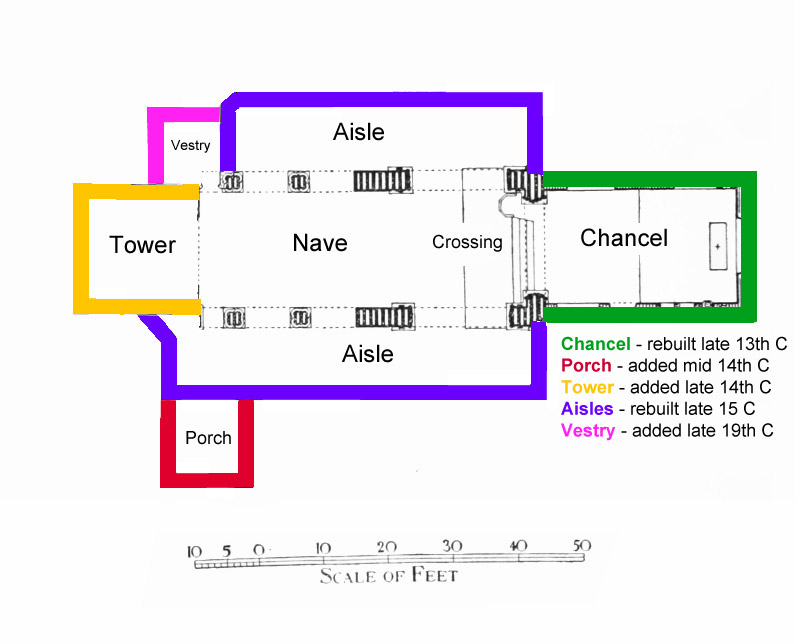

The south porch was added to the entrance around 1350 and the tower about 1380. The original minster may have extended further than the tower. From the outside, a partial arch can be seen adjoining the tower in the clerestory (upper part of the nave above the lower roof). The lower roof on the south side is mirrored by one on the north; these are aisles that were present originally but were rebuilt in the late 1400's extending further than originally at the eastern end as the transepts were now gone, but cut short at the western end as they no longer enclosed the tower as they did the previously longer nave. In 1880 a small vestry was added to the north side adjacent to the tower.

The minster would have had a thatched roof and possibly a short tower above the "crossing", where the short and long parts of the cross shape met. There is no record of the form of this tower, though from other similar buildings, it may have taken the form of a short wooden spire rather than being a square tower.

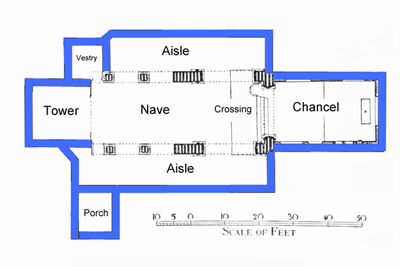

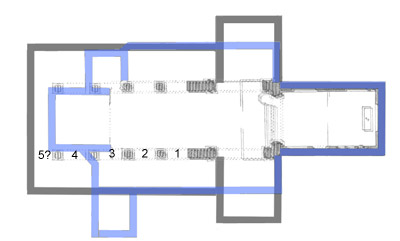

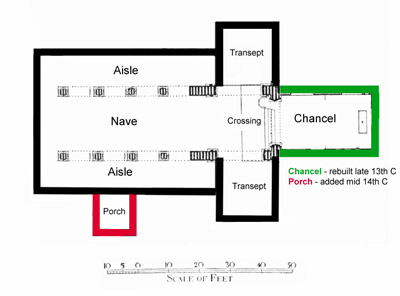

The simplified plans of the original minster and the modern church overlaid. Where some walls are in the same place, they may have been rebuilt, for instance the chancel and aisles are where they always were but are now not the original ones. The numbers refer to the nave arches, three survive today there was probably a 4th and possibly a 5th.

1020 - A plan of the original minster.

The exact position of the western (left) wall and therefore

the overall length of the church is not known. Presently

there are 2 1/2 arched bays to the south aisle (after

some odd building work altered the 3rd) and the proportions

and position of the door imply that there was certainly

at least a fourth arch. A fifth would give the minster

better proportions, though there is no evidence to say

that this ever existed.

The footprint of the original minster was about 10-20% greater compared to the current church depending if there were 4 or 5 arched bays in the nave, and it would have seemed larger and more impressive on the inside due to the full height of the longer nave and the presence of the two transepts.

When and Why was the Church Remodelled?

While we know 'what' changes were made to the church after its initial construction and approximately 'when', the 'whys' are less clear.

250+ years, late 1200's. The first major change was when the chancel was rebuilt following a collapse, though the extent of this collapse is unrecorded and may have been figurative with cracks, bulging and subsidence rather than a literal heap of masonry on the ground.

The crossing is supported by four pillars and there is an arch to the north and south. The pillars and arch are now notably taller at the north side than the south, and those at the south have been altered in a way not repeated in the north. This is taken by some as an indication that a tower supported above the crossing collapsed to the south, so damaging the southern arch and possibly the chancel with it. Another view is that the pillars and four arches of the crossing are not substantial enough to have supported a tower and a short wooden spire would be a more likely adornment, though of course this does not preclude its collapse and resultant damage. Another 200+ years later, around about 1500, buttresses were added to the chancel to support it, with an extra one at the north east added in 1520 in response to settlement. In 1902, the chancel was underpinned and was found to be resting on the earth with no real foundations.

After the chancel rebuilding, the church will still have been essentially the same as when it was first built, though it is possible the east end was originally apsidal (rounded).

330 years, about 1350. The porch on the south side was added attached to an aisle that was later removed and rebuilt. It is in line with the third arch of the internal arcade and there will almost certainly have been a fourth arch to the west (left) of the porch, so when built it would not have been at the end as it is now. There are stone seats along each side of the porch where "jurors" would have sat as witnesses to weddings prior to the introduction of church registers in 1538. There are two windows on the sides of the porch which are more recent additions.

The door into the church from the porch is very old and is adorned with elaborate ironwork which may be older still from the late 1200's, possibly from the original Saxon door to the church.

360 years, about 1380. A large change in the appearance of the church came with the building of the tower at the western end of the nave. By the middle of the 1300's the structure above the crossing, a tower or wooden spire is thought to have become unsafe and was removed (unless it collapsed in the late 1200's). Two diagonally opposite pillars at the crossing lean slightly outwards which has been suggested is indicative of being pushed out by a weight above them, though lines being off true vertical or horizontal are very common in old buildings.

The building of the tower required the removal of part of the western end of the nave, taking it down from 4 or 5 arches long to 2 1/2 on the south side (3 in size equivalent to the outside wall). It will also have meant the removal of part of the adjoining aisles that flanked the nave. This will have reduced the size of the nave for congregations by 25% or more, so why did it happen?

By now, the original missionary function of the minster church was over as local parish churches built after the minster now served their own villages and congregations. The nearby villages of Little Paxton, Toseland and Abbotsley all had their own churches and while Great Paxton was the "Mother" church, there would have been fewer people attending on a regular basis. This doesn't explain why what must no doubt have been costly changes were made at this time rather than leaving things as they were. No record exists to explain why but perhaps at least in part, if this end of the church had suffered damage in a similar manner to the chancel just over a century before and as repair was needed, the opportunity was taken to make a church that was more in keeping with the time and contemporary building trends, now that the Anglo-Saxon era was long over.

The church now looks more like what we recognise today, though the transepts are still standing.

450+ years, late 1400's. The final major structural change to the church occurred when the transepts were removed and the aisles rebuilt and extended past where the transepts used to be and flush with the eastern end of the nave. The northern side was removed first followed by the southern side.

The "lean-to" roof of the aisles were probably placed higher up than originally covering the bottom half of the clerestory windows, this roof can be seen in the earliest photographs of the church when the clerestory windows are also filled in though this may have happened at a later date.

Again there is no record as to why these changes were carried out, we can only surmise that perhaps a combination of damage to the transepts and aisles combined with the opportunity to again remodel the church according to then trends in architecture and what was required by the community led to the redesign.

These last changes resulted in the church that we see today which in its major components has now been unchanged for over 500 years.

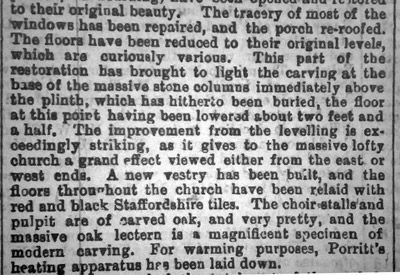

860 years, 1880. A small vestry was added to the north side of the tower with a fireplace, and an under-floor heating system in the body of the church, just outside a coal cellar was placed nearby. This was a time of major renovation, the previously boarded over clerestory windows were restored to their former condition, the floor level was reduced by around 2 feet (see more below) and new black and red tile flooring was installed.

989 years, 2009. The ringing floor where the bell ringers stand was raised so that another "storey" was made in the tower, in the space under this new ringing floor (the original ringing floor) toilets and a kitchenette/servery was added.

999 years, 2019. In the summer of 2019 the chancel was reroofed and four chancel windows re-leaded and cleaned.

The Bells

The first bell was cast and installed in about 1400 not long after the tower was built. The bells were brought to Great Paxton by the river and unloaded at "Bell Ford". It is not clear whether a ford already existed at this place and was renamed or if it was made at the time to enable them to be unloaded from the boat that was carrying them; this also gave its name to the adjacent "Bell Ford Meadow".

All but one of the original bells from 1400 have been recast over the years, but from 1972 they worsened in condition despite attempts to restore them until becoming virtually un-ringable by 2016. In 2018, the bells were removed from the tower following a community fund raising effort with assistance from the National Lottery and were then completely refurbished at John Taylor & Co. bell foundry in Loughborough. There are now six bells which are rung by local and visiting ringers on a regular basis. The headstocks of the bells have all been locally sponsored and all have dedications to those who did so. There is an amount of graffiti going back centuries in the middle chamber of the tower.

A raised ringers floor was added to the tower in 2009 which is accessed by an oak staircase. This means that the bell ringers are now no longer at ground level freeing up space on the ground floor which was in part used to introduce badly needed facilities. In the process of adding these, the floor was dug up and stonework dating back to Saxon times unearthed, possibly from the structure of the church itself, possibly stonemasons hidden mistakes and possibly a Saxon gravestone.

More on the Great Paxton Bells Project here

The Raised Floor

From the Huntingdonshire Gazette, 26th June 1880. |

There is a casual mention by a former vicar of Great Paxton, the Reverend Cane, in a 1906 publication that states:

"When the church was restored in 1867 the floor of the church was lowered, some two feet, to its original level".

Now look at where you are sitting, 2 feet will most likely be more than the distance from the floor to the top of your thigh. Imagine that space in the room you are in being filled solidly with stone, rubble, gravel, soil etc. to that height. That is what the church was like until it was all cleared out again in 1867. A rough calculation of the area of the church nave and aisles covered to that depth gives a figure of over 4,500 cubic feet of material weighing in excess of 500 tonnes. Rev. Cane goes on to describe how much more impressive the chancel and altar now seem when they are another 2 feet higher than the nave and aisles.

All of this was added at some time between its construction in 1020 and 1867 to the inside of the church to raise the level of the floor, why?

There are no other clues or records of why this was done, so we have to rely on evidence and conjecture (you may have to indulge me here).

A clue is given by the church today where there are areas in the aisles and the steps up to the chancel that periodically need to be cleaned of algae that can persist even in the summer. The ground is damp and pulls up water from the water table even in dry weather. Recently (autumn 2019) floor joists under the pews on one side had to be replaced after becoming rotten with a rich crop of fungi growing on them even in midsummer, a result the of the constant damp.

In the 1700's, the fens were drained. The nearby river Great Ouse flows through the fens and this would have had the effect of lowering the water level along a significant portion of the river upstream. Between the church and the river (500m away) would have been water meadow all along the river to about the level of the railway line (125m away). In the historical past it would have been possible to come from the river to the edge of the water meadow along shallow ditches in small boats and barges as probably happened originally to bring the raw materials to supply the lime kilns described above that made lime to build the church, along with much if not all of the dressed stone used to build the church. This means that the water table would have been higher than now and presumably the damp problem in the church would have been much worse.

September 2019, the floor boards under part of the pews removed to repair joists rotted by fungus (the white patches) that has thrived in the very damp atmosphere despite vents allowing for air flow. The floor board level is about 25cm (10") above the actual earth floor of the church which can be seen. The base of a pillar can be seen at the top of the first picture, the 2 feet of material would have stretched to about the top of the white area. On the edge of the bottom of the second picture can be seen three courses of bricks which support the Victorian black and red tiled floor put in during the 1867 restoration.

I suggest that all that material in the church was put there to raise the level of the floor away from encroaching significant damp. The source of such large amounts of material possibly being the replacement and removal of various parts of the church over the years, the replaced chancel, parts of the aisles removed when the tower was built, the remainder of the aisles when they were replaced, and the removed transepts.

After the fens were drained, the problem with damp may have been reduced significantly and there was no further need for the elevated floor and so it was removed when the major restoration in 1867 came round.